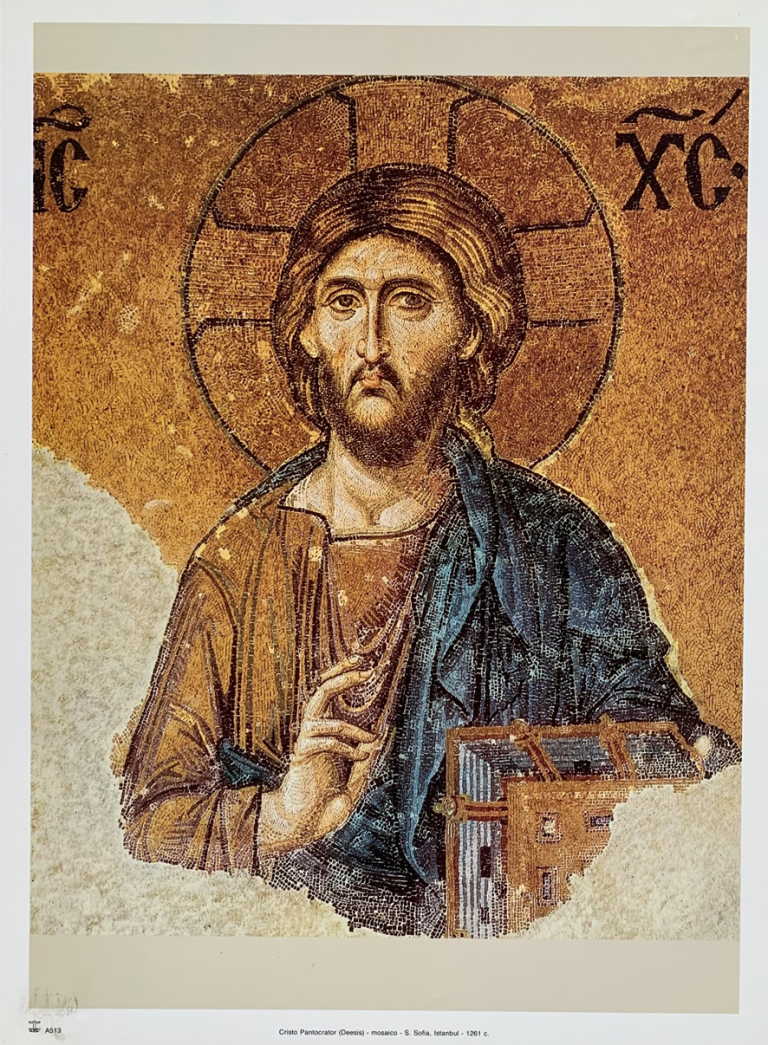

Jesus Pantocrator – Hagia Sofia, Istambul – sec XIII

“Eu sou o Alfa e o Ômega, o começo e o fim.” diz o Senhor:

“Quem é, Quem foi e Quem há de vir, o Pantrocrator.”

(Livro do Apocalipse 1 : 8)

Jesus Cristo da “deésis” de Santa Sofia

Jesus Pantocrator – Hagia Sofia, Istambul – sec XIII

Cristo Jesus dulcíssimo, Jesus pacientíssimo, cura as chagas da minha alma, Jesus misericordiosíssimo, eu te suplico: abranda o meu coração, a fim de que, salvo por ti, Jesus meu Salvador, eu te renda glória.

Meu Jesus, amigo dos homens, escuta a voz, compungida do teu servo, Jesus pacientíssimo, livra-me da condenação e do castigo, Jesus dulcíssimo e piedosíssimo. Meu Jesus, eu te suplico: cura as feridas da minha alma, livra-me das mãos de Beliar corruptor das almas e dá-me a salvação, ó meu Jesus misericordiosíssimo.

Ó meu Jesus, Salvador, tu és a luz da minha mente e a salvação da minha alma misera; meu Jesus, livra do castigo e da geena a mim que a ti clamo: a meu Cristo Jesus, salva-me a mim miserável!

Jesus dulcíssimo, luz do mundo, ilumina os olhos da minha alma com o esplendor da tua luz, a fim de que, ó Filho de Deus, eu proclame a tua luz sem ocaso. Meu Jesus, eu te suplico: como livraste, ó meu Jesus, a meretriz dos seus numerosos pecados, livra-me também a mim, ó meu Cristo Jesus, e purifica, ó meu Jesus, a minha alma manchada.

Jesus dulcíssimo, desejo da minha alma, purificação da minha mente, Senhor rico em misericórdia, Jesus, salva-me; Jesus, meu Salvador, meu Jesus poderosíssimo, não me abandones; Jesus Salvador, tem piedade de mim, e salva-me de toda condenação, e torna-me digno, ó Jesus, da sorte dos salvos, ó meu Jesus; e conta-me no coro dos eleitos, Jesus amigo dos homens.

TEOSTERICTO MONGE (séc. IX), Cânon a Jesus dulcíssimo.

O Cristo Pantocrator da Agia Sofia

O Cristo aqui reproduzido constitui a parte central de uma “Deésis” a três figuras (trimorphon), na qual Cristo é ladeado, à direita, pela Mãe de Deus, à esquerda, por João Batista, voltados para ele em atitude de súplica (é este o sentido do termo “deésis”).

O mosaico, de grande dimensões (595 x 408 cm) e de rara beleza, está muito danificado, mas o essencial da figura providencialmente se salvou, oferecendo um espetáculo cheio de fineza e de fatos.

A “Deésis”, enquadrada num espesso friso colorido, ocupa a arcada central da galeria do lado sul da catedral de santa Sofia, obra-prima arquitetônica terminada pelo imperador Justiniano em 537 e que se tornou, desde então, o coração da história e da piedade da capital bizantina.

A igreja de santa Sofia, de fundação constantiniana, destruída por um incêndio em 532, foi totalmente reconstruída por Justiniano, num lapso de tempo extraordinariamente breve: cinco anos e dez meses (532-537).

A atual cúpula, reconstruída em 562, se eleva a 54 metros do chão com um diâmetro de 31 metros, superando em altura a do Panteão de Roma (43 metros) e as abóbadas das catedrais góticas.

A decoração da basílica de Justiniano era constituída de grandes placas de mármore policromo e de mosaicos figurativos. Esses últimos foram irremediavelmente danificados, primeiro durante a luta iconoclasta (séc. VIII-IX), depois durante a ocupação de Constantinopla pelos latinos (1204-1261); mas foram restaurados com maior esplendor no período sucessivo.

Em 1453, os turcos, ocupando a cidade, transformaram a igreja em mesquita, destruindo muitos mosaicos e cobrindo o resto de gesso e cal. Em 1935 a mesquita foi transformada em museu; isto permitiu ao Instituto Bizantino da América proceder a restaurações e trazer a luz o que tinha ficado da decoração anterior, inclusive a “deésis” de que estamos falando.

O mosaico em questão é pouco posterior à libertação de Constantinopla da ocupação latina, e se coloca no início do último período da arte bizantina, o dos Paleólogos (1259-1453), em que a arte, fruto de um renascimento humanístico, atingirá o máximo esplendor somente nos últimos dois séculos do Império bizantino.

“A obra segundo V. Lazarev, famoso historiador da arte bizantina é sem dúvida devida a insignes mestres da capital bizantina, os quais atingiram, com os meios da arte do mosaico, efeitos pictóricos altamente refinados.

Possuindo um excepcional e preciso senso da cor, eles se comprazeram em enriquecer a cor básica das vestes com uma série de tons complementares graças aos quais a gama cromática adquiria uma insólita delicadeza.

Assim o manto verde do Batista, que recorda a cor das ondas do mar, é composto do verde claro, do verde grisalho, do azul e do negro.

Algo semelhante se encontra no manto violáceo de Maria e no azul de Cristo. Segundo o mesmo autor, os rostos profundamente espirituais são trabalhados minuciosamente: as ligeiras sombras esverdeadas têm uma maravilhosa transparência, as passagens das luzes às sombras são quase imperceptíveis, nas partes mais iluminadas utilizam-se amplamente pedrinhas rosas e brancas de delicadíssimos matizes”.

As figuras de Maria e do Batista correspondem às da Esposa e do Amigo do Esposo, porque Cristo se revela como o Esposo da alma que vem a ele “com fé e amor”, como diz o sacerdote que convida o povo à comunhão.

O rosto do Batista é macerado pela penitência, o da Mãe de Deus é extraordinariamente radiante. Mas seus olhos são os de quem chorou muito, chorou tanto que suas lágrimas se tornaram lágrimas de alegria: “Não chores, Mãe, eu ressuscitarei”.

São João é a ascese viril que dissolve o ego individual: “É preciso que ele cresça e que eu diminua”.

A Theotokos, a Mãe de Deus, é a pessoa abatida pelas lágrimas e recriada pelo Espírito Santo, segundo uma feliz expressão do patriarca Atenágoras’.

Cristo está representado segundo a tipologia do Pantocrator.

Devia aparecer de corpo inteiro, não se sabe se de pé ou sentado no trono, mas restou só o meio busto que se destaca no fundo dourado, que devia recobrir toda a parede inundando de luz as personagens.

Das inscrições, sobraram apenas os digramas IC XC, de um e de outro lado da cabeça, escritos em belas letras gregas maiúsculas.

Na grande auréola de cor ouro sobressai claramente a cruz patente, com as extremidades dos braços que se alargam.

Cristo veste túnica de cor ouro, que deixa ver – do corpo – apenas o pescoço e a mão direita que abençoa “à maneira grega”, com o dedo mínimo muito curvado.

O manto de cor azul claro, que mal se vê sobre o ombro direito, cobre o esquerdo e desce sobre o peito.

A mão esquerda – que desapareceu sobre a imagem – segura um grande livro parcialmente conservado, fechado com fechos, ricamente ornado e apoiado no peito.

A figura de Cristo, apesar de corresponder – em grandes linhas -à do Cristo do Sinai e a outros ícones mais recentes que vimos anteriormente, dá-nos entanto a impressão de algo totalmente novo. A forma do nariz, o queixo marcado, o bigode caído, as sobrancelhas fortemente traças conferem ao rosto decisão e severidade.

As faces finamente modeladas, os cabelos ondulados e o olhar sereno fazem dessa figura de Cristo, não obstante toda a sua majestade de Juiz e a grandiosidade sobre-humana, o Cristo todo penetrado de doçura e de bondade, o Salvador rico em misericórdia, a própria encarnação do amor e da bondade.

É também o Jesus dulcíssimo cantado pelo monge estudita Teostericto (séc. IX), como consta das estrofes colocadas diante da imagem.

The Christ of the “deesis” of Saint Sophia (mosaic, 13th century)

Christ Jesus most sweet, Jesus most patient, heal the wounds of my soul, Jesus most merciful, I beg you: soften my heart, so that, saved by you, Jesus my Savior, I may give you glory.

My Jesus, friend of men, listen to the compassionate voice of your servant, most patient Jesus, free me from condemnation and punishment, most sweet and most pious Jesus. My Jesus, I beseech you: heal the wounds of my soul, free me from the hands of Beliar, corrupter of souls, and give me salvation, O my most merciful Jesus.

Oh my Jesus, Savior, you are the light of my mind and the salvation of my miserable soul; My Jesus, free me from punishment and Gehenna who cry out to you: to my Christ Jesus, save me, my wretched one!

Most sweet Jesus, light of the world, illuminate the eyes of my soul with the splendor of your light, so that, O Son of God, I may proclaim your light without fail. My Jesus, I beg you: as you freed, O my Jesus, the harlot from her many sins, free me also, O my Christ Jesus, and purify, O my Jesus, my stained soul.

Most sweet Jesus, desire of my soul, purification of my mind, Lord rich in mercy, Jesus, save me; Jesus, my Savior, my most powerful Jesus, do not abandon me; Jesus Savior, have mercy on me, and save me from all condemnation, and make me worthy, O Jesus, of the fate of the saved, O my Jesus; and tell me in the choir of the elect, Jesus friend of men.

THEOSTERICTO MONGE (9th century), Canon a Jesus dulcissimo.

The Christ Pantocrator of Aghia Sophia

The Christ reproduced here constitutes the central part of a “Deesis” with three figures (trimorphon), in which Christ is flanked, on the right, by the Mother of God, on the left, by John the Baptist, facing him in an attitude of supplication. (this is the meaning of the term “deesis”).

The mosaic, large (595 x 408 cm) and of rare beauty, is very damaged, but the essential part of the figure was providentially saved, offering a spectacle full of finesse and pathos. The “Deesis”, framed in a thick colored frieze, occupies the central arcade of the gallery on the south side of Saint Sophia Cathedral, an architectural masterpiece completed by Emperor Justinian in 537 and which has since become the heart of history and the piety of the Byzantine capital.

The church of Saint Sophia, of Constantinian foundation, destroyed by a fire in 532, was completely rebuilt by Justinian, in an extraordinarily brief period of time: five years and ten months (532-537). The current dome, rebuilt in 562, rises 54 meters from the ground with a diameter of 31 meters, surpassing in height that of the Pantheon in Rome (43 meters) and the vaults of Gothic cathedrals. The decoration of Justinian’s basilica consisted of large polychrome marble slabs and figurative mosaics.

The latter were irreparably damaged, first during the iconoclastic struggle (8th-9th century), then during the occupation of Constantinople by the Latins (1204-1261); but they were restored with greater splendor in the succeeding period. In 1453, the Turks, occupying the city, transformed the church into a mosque, destroying many mosaics and covering the rest with plaster and lime. In 1935 the mosque was transformed into a museum; This allowed the Byzantine Institute of America to carry out restorations and bring to light what was left of the previous decoration, including the “deesis” we are talking about.

The mosaic in question is shortly after the liberation of Constantinople from Latin occupation, and is placed at the beginning of the last period of Byzantine art, that of the Palaiologos (1259-1453), in which art, the result of a humanistic renaissance, reached its maximum splendor only in the last two centuries of the Byzantine Empire.

“The work according to V. Lazarev, famous historian of Byzantine art – is undoubtedly due to distinguished masters from the Byzantine capital, who achieved, with the means of mosaic art, highly refined pictorial effects. Possessing an exceptional and precise sense of color, they took pleasure in enriching the basic color of the clothes with a series of complementary tones thanks to which the chromatic range acquired an unusual delicacy.

Thus the Batista’s green cloak, which recalls the color of the sea waves, is composed of light green, gray green, blue and black. Something similar is found in the violet mantle of Mary and in the blue of Christ. According to the same author, the deeply spiritual faces are worked on in detail: the light greenish shadows have a wonderful transparency, the passages from light to shadow are almost imperceptible, in the most illuminated parts pink and white pebbles of very delicate hues are widely used”2.

The figures of Mary and the Baptist correspond to those of the Wife and the Husband’s Friend, because Christ reveals himself as the Spouse of the soul who comes to him “with faith and love”, as the priest who invites the people to communion says. The face of the Baptist is macerated by penance, that of the Mother of God is extraordinarily radiant.

But her eyes are those of someone who cried a lot, cried so much that her tears became tears of joy: “Don’t cry, Mother, I will rise again.” Saint John is the virile asceticism that dissolves the individual ego: “He must grow and I must diminish.” The Theotokos, the Mother of God, is the person cast down by tears and recreated by the Holy Spirit, according to a happy expression of the patriarch Athenagoras’.

Christ is represented according to the Pantocrator typology. It should have appeared in full body, it is not known whether standing or sitting on the throne, but only the half-bust remained, which stands out against the golden background, which should cover the entire wall, flooding the characters with light. From the inscriptions, only the IC XC digrams remained, on both sides of the head, written in beautiful capital Greek letters. In the large gold-colored halo, the patent cross clearly stands out, with the ends of the arms widening.

Christ wears a gold-colored tunic, which reveals – of his body – only his neck and his right hand which he blesses “in the Greek way”, with the little finger very curved. The light blue cloak, which can barely be seen over the right shoulder, covers the left and descends over the chest. The left hand – which has disappeared over the image – holds a large, partially preserved book, closed with clasps, richly decorated and resting on the chest.

The figure of Christ, despite corresponding – in broad terms – to the Christ of Sinai and other more recent icons that we have seen previously, nevertheless gives the impression of something totally new. The shape of the nose, the marked chin, the drooping mustache, the strongly drawn eyebrows give the face decision and severity.

The finely modeled faces, the wavy hair and the serene look make this figure of Christ, despite all his majesty as a Judge and superhuman grandeur, the Christ completely permeated with sweetness and kindness, the Savior rich in mercy, the very incarnation of love and kindness. It is also the very sweet Jesus sung by the student monk Theosterictus (9th century), as stated in the stanzas placed in front of the image.

Source: Vida de Cristo em Ícones.

Produzido por / Organized by: MuMi – Museu Mítico

Consulte a Agenda do Museu a partir de 2025 e o visite quando receber sua confirmação de visita em seu email ou whatsapp.

Por se tratar de um museu particular, é necessário se cadastrar na Comunidade MuMi e customizar sua visita.

Criação e Tecnologia: Clayton Tenório @2025 MuMi – Museu Mítico