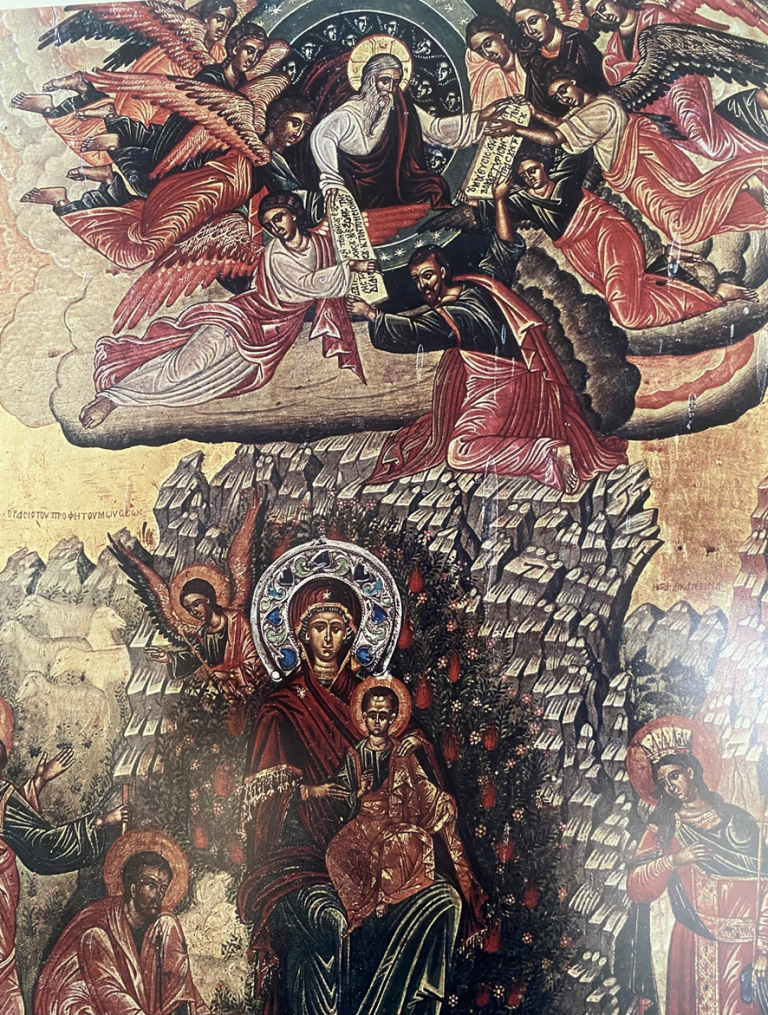

Virgem na Sarça Ardente – Michael Damaskenos – sec. XVI – Monastério de Santa Catarina do Sinai

Moisés e o Fogo Sagrado e a Virginidade da Sagrada Mãe de Deus (Theotokos)

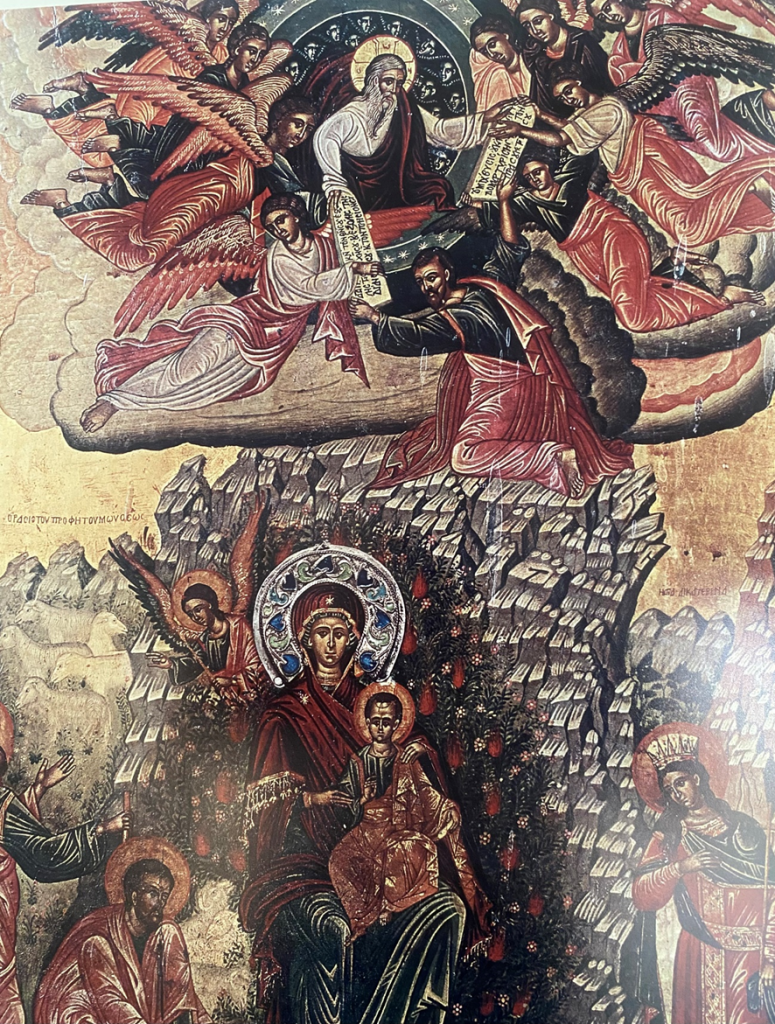

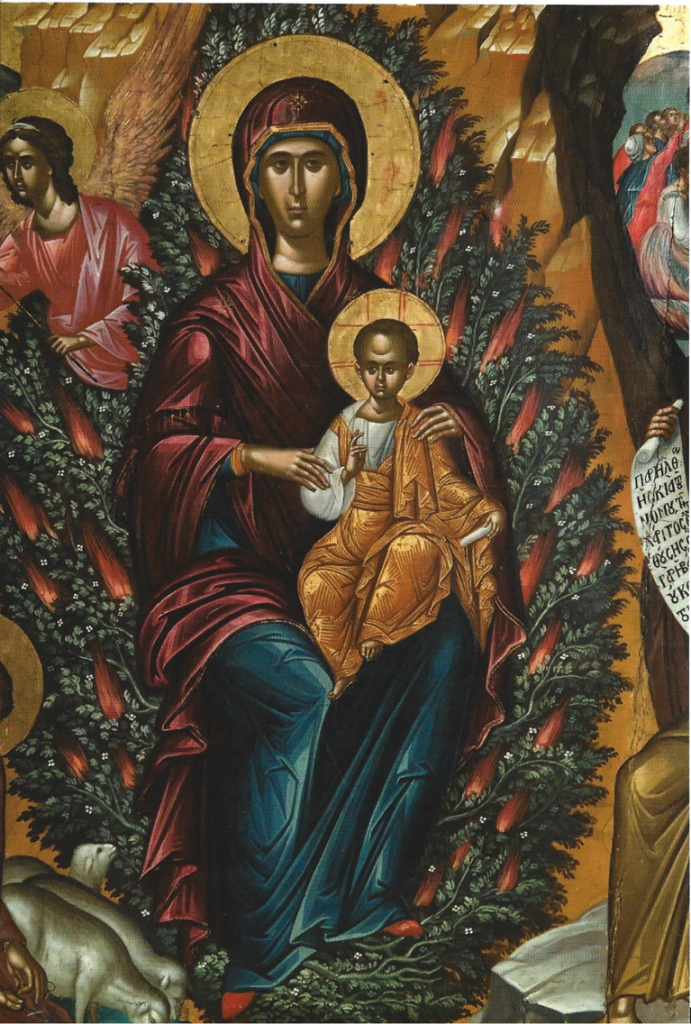

Detalhe da Virgem na Sarça Ardente – Michael Damaskenos – sec. XVI –

Monastério de Santa Catarina do Sinai

O profeta Moisés ocupa um lugar importante na revelação de Deus, que pela primeira vez fala ao homem e revela os seus planos. O chamado de Moisés e a revelação da vontade de Deus foram escolhidos pela Divina Providência para acontecer no Monte Sinai.

Depois de quarenta anos de oração, enquanto pastava suas cabras no Monte Coreb, Moisés encontrou o grande mistério da “sarça que queimou e ficou sem ser consumida” e ouviu a voz do Senhor chamando seu nome e pedindo-lhe que tirasse as sandálias, como o chão que ele pisava era sagrado.

A Igreja interpretou a visão de Bush como um prenúncio do mistério do nascimento da Mãe de Deus. Enquanto Bush estava queimando, mas permaneceu sem consumo. então a Theotokos após a encarnação do Logos permaneceu sempre virgem.

Neste local mais sagrado da Bush, o Mosteiro de Sinai foi fundado vários séculos depois e, segundo os escritos de Procopios, historiador pessoal do imperador Justiniano dedicado à Theotokos, cuja veneração esteve durante muito tempo ligada ao Fogo Sagrado do Burning Bush.

Alguns dos primeiros ícones do mosteiro que sobreviveram oferecem-nos uma visão particularmente valiosa sobre a história dos ícones na vida religiosa, pois enfatizam a importância da Theotokos, que também é representada com Fogo Sagrado na iconografia.

Desde o século XI, Moisés também está ligado à Theotokos pela Sarça Ardente na iconografia, e vários outros ícones retratam tanto as figuras sagradas quanto o local sagrado.

Moisés, porém, é novamente chamado a subir ao santíssimo Monte Sinai e abençoá-lo, já que esse seria o local onde Deus desceria para apresentar as suas leis e os seus Mandamentos.

Esta ocorrência, após a qual a Montanha passou a ser chamada de Theovadiston (Pisado por Deus) – se tornará um tema importante na iconografia do Sinai, que retrata explicitamente o local e a Revelação de Deus. Contudo, Moisés apenas ouviu a voz de Deus e não viu o Seu rosto no Monte Sinai.

Esse rosto seria revelado a Moisés durante a Transfiguração de Jesus Cristo. Os artistas de Justiniano representariam mais tarde este magnífico evento no grande mosaico da abside da basílica.

As sagradas relíquias da grande mártir Santa Catarina foram milagrosamente descobertas em algum momento do século X, ou mesmo antes, e transportadas para o mosteiro para serem guardadas. Gradualmente, o mosteiro transferiu sua dedicação e o Santa foi acrescentada à iconografia do Sinai.

No início ela foi associada à Virgem da Sarça e apareceu entre outros santos e profetas, mas mais tarde sua vida foi retratada e foi associada à Theotokos e a Moisés. De qualquer forma, a veneração de Santa Catarina se espalhou e ela gradualmente se tornou a santa do Sinai, dominando a iconografia relevante.

A Theotokos e Moisés mantêm seus lugares como portadores das revelações de Deus e da santidade geral do local.

Os tesouros religiosos, uma herança sagrada de ícones, manuscritos, vasos litúrgicos e vestimentas que foram acumulados ao longo dos séculos e agora são preservados no Sinai, a verdadeira fortaleza da fé ortodoxa, são os testemunhos materiais destes eventos sagrados, e da profunda fé dos peregrinos.

GG

Fonte: The Monastery of Mount Sinai and its Sacristy – 2020, pg 27.

As Obras de Michael Damaskenos

Michael Damaskenos criou um grande número de obras de arte, hoje em museus, igrejas, coleções privadas e públicas na Grécia (Athos, Atenas, Galaxeidi, Zakynthos, Corfu, Creta, uma vez no mosteiro de Hosios Lukas, Patmos), Itália (Veneza, Convensano na Apúlia, Roma), o Monte Sinai, coleções particulares na América etc.

Mais de cem ícones são atribuídos a ele, metade deles com base em critérios históricos e estilísticos (não assinados). Apenas dois têm data, a decapitação de São João Batista em Corfu (1590) e o Primeiro Sínodo Ecumênico no Museu de Santa Catarina em Herak (1591).

Ele pintou ícones de grande escala para igrejas e mosteiros, mas também ícones menores e trípticos para uso privado. Um grande número de suas obras segue a tradição do Paleologano Tardio – iconografia cretense primitiva, como o ícone de Simeão com o Cristo na igreja de São Mateus em Heraklion, o ícone de Santo Antônio no Museu Bizantino de Atenas, o profeta Elias no mosteiro de Stavronikita (Athos), muitos dos ícones da igreja de São Jorge em Veneza, etc.

Muitas outras obras são influenciadas pelas pinturas e gravuras italianas do Renascimento e do Maneirismo, como a Crucificação de Santo André no Museu Bizantino de Atenas, a Lamentação na igreja de São Jorge em Veneza, o Martírio de Santo Paraskevi no Museu Kanelopoulos em Atenas e uma série de ícones em Corfu.

Moses and the Burning Bush and the Virginity of the Blessed Theotokos (the mother of God)

The Prophet Moses holds an important place in the revelation of God, who for the first time speaks to man and reveals His plans.

Moses’ call and the revelation of the will of God were chosen by Divine Providence to take place on Mount Sinai. Following forty years of prayer, as he was grazing his goats on Mount Choreb, Moses encountered the great mystery of the “Bush that burned yet remained uncosumed” and heard the voice of the Lord calling his name and asking him to remove his sandals, as the ground he was treading on was sacred.

The Church interpreted the vision of the Bush as a foreshadowing of the mystery of the childbirth of the Mother of God. As the Bush was burning but remained uncosumed, so the Theotokos after the incarnation of the Logos remained ever Virgin.

At this most sacred site of the Bush, the Sinai Monastery was founded several centuries later and, according to the writings of Procopios, personal historian of emperor Justinian dedicated to the Theotokos, whose veneration had been long linked to the Holy Bush.

Some early surviving icons of the monastery offer us particularly valuable insight into the his tory of icons in religious life, as they empha size the importance of the Theotokos, who is represented by the Bush in iconography as well.

Since the eleventh century, Moses is also linked to the Theotokos of the Bush in iconog raphy, and several other icons depict both the holy figures and the sacred site.

Moses, though, is again called on to ascend the most sacred Mount Sinai, and bless it, since that would be the site where God would descend to present Moses with His Law and His commandments.

This occurrence after which the Mountain as also name Theovadiston (God-Trodden) – will become a major theme in Sinai iconography which explicitly depicts the site and the Revelation of God. However, Moses only heard the voice of God and did not see His face on Mount Sinai.

That face would be revealed to Moses during the Transfiguration of Jesus Christ. Justinian’s artists would later depict this magnificent event in the grand mosaic in the apse of the basilica.

The holy relics of the great martyr Saint Catherine were miraculously discovered some time in the tenth century, or even earlier, and transported to the monastery for safekeeping. Gradually the monastery transferred its dedication, and the Saint is added to the Sinai iconography.

At first she was associated with the Virgin of the Bush, and appeared among other saints and prophets, while later on, her life was depicted, and she was associated with the Theotokos and Moses. At any rate, the veneration of Saint Catherine spread, and she gradually became the saint of Sinai, dominating the relevant iconography.

The Theotokos and Moses retain their places as bearers of God’s revelations, and the overall sanctity of the site. The religious treasures, a sacred inheritance of icons, manuscripts, liturgical vessels, and vestments which have been accumulated over the centuries and are now preserved in Sinai, the veritable fortress of Orthodox faith, are the material testaments to these holy events, and to the profound faith of pilgrims.

Source: The Monastery of Mount Sinai and its Sacristy – 2020, pg 27

The painting of Michael Damaskenos

Michael Damaskenos created a large number of art works, today into museums, churches, private and public collections in Greece (Athos, Athens, Galaxeidi, Zakynthos, Corfu, Crete, once at the monastery of Hosios Lukas, Patmos), Italy (Venice, Convensano in Apulia, Rome), the Mount Sinai, private collections in America etc.

More than one hundred icons are attrib uted to him, half of these on historic and stylistic crite ria (unsigned). Only two bear a date, the Beheading of Saint John the Baptist in Corfu (1590) and the First Ecumenical Synod in the Museum of St. Catherine in Herak lion (1591).

He painted large-scale icons for churches and monas teries, but also smaller icons and triptychs for private use. A large number of his works follow the tradition of the Late Paleologan – Early Cretan iconography, such as the icon of Symeon with the Christ in the church of St. Mathew in Heraklion, the icon of St. Antony in the Byz antine Museum of Athens, Prophet Elias in the monas tery of Stavroniketa (Athos), many of the icons in the church of St. George in Venice etc.

Many other works are influenced by the Italian paint ings and engravings of the Renaissance and the Man nerism, such as the Crucifixion of Saint Andrew in the Byzantine Museum of Athens, the Lamentation in the church of St. George in Venice, the Martyrdom of Saint Paraskevi in the Kanelopoulos Museum in Athens, and a series of icons in Corfu.

Produzido por

Consulte a Agenda do Museu a partir de 2025 e o visite quando receber sua confirmação de visita em seu email ou whatsapp.

Por se tratar de um museu particular, é necessário se cadastrar na Comunidade MuMi e customizar sua visita.

Criação e Tecnologia: Clayton Tenório @2025 MuMi – Museu Mítico