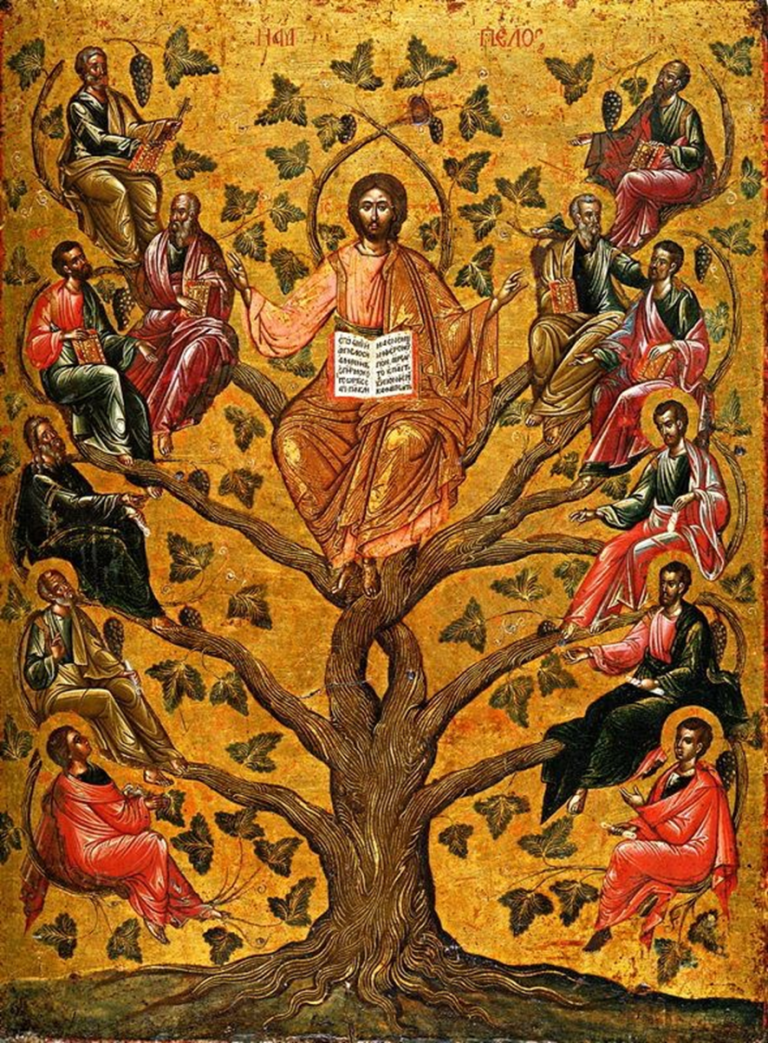

Jesus Cristo e os Apóstolos na árvore da vida – autor desconhecido

CRISTO “VIDEIRA VERDADEIRA” (ícone, cerca de 1450)

Vejamos ainda por que o nosso Salvador comparou-se a si mesmo à videira.

“Eu sou a verdadeira videira e o agricultor é o meu Pai”. Na videira do seu corpo foi escondida a doçura da sua divindade; na videira do seu corpo foi enxertado o sarmento e o raminho da nossa humanidade. Da videira do seu corpo, para nós brotou a bebida que saciou a nossa sede. Do raminho da sua humanidade rios fluíram para nós por sua graça.

Cala-se a videira quando colhem a uva, como o Senhor nosso quando o julgam; cala-se a videira, quando é despojada, como o Senhor nosso quando é ultraja- do; cala-se a videira, quando a podam, como o Senhor nosso, quando o matam.

Em vez daquela videira antiga, que ofereceu vinagre ao seu dono, uma videira de verdade despontou para nós do seio da jovem. Esta é a videira, que inebriou os homens e possuíram a vida; esta é a videira, que, com o seu fruto, o mundo lava das iniqüidades.

É o cacho que espremeu a si mesmo no Cenáculo, na hora vespertina, e no cálice se deu aos seus discípulos, que é o testemunho de verdade, porque a sua riqueza jamais diminui.

CIRILLONA, Discurso da última ceia

A “VIDEIRA VERDADEIRA”

O tema iconográfico de Cristo “Videira verdadeira” se inspira na alegoria evangélica de Jo 15,1ss. Aí Jesus se equipara à videira, compara o seu Pai ao vinhateiro, enquanto seus discípulos são assimilados aos ramos. A união destes ao tronco é a condição para dar frutos e ser amados pelo Pai. Em caso contrário, eles são cortados, deixados secar e lançados no fogo.

A ilustração iconográfica do tema é relativamente recente e parece suscitada pelo desejo dos iconógrafos de tratar argumentos novos total- mente ignorados no passado, ou pelo menos escassamente tratados até então. As primeiras representações remontam ao séc. XV e parecem todas posteriores à queda de Constantinopla nas mãos dos turcos em 1453. Terra de origem foi a ilha de Creta, onde se tinham refugiado muitos artistas fugindo dos turcos, e os mosteiros do monte Athos, que lhes ofereciam enormes espaços para ornar de afrescos e de ícones.

O tema, surgido no séc. XV, torna-se freqüente em afrescos e em ícones do séc. XVI e se multiplica no séc. XVII; encontra-se também em muitos paramentos sacerdotais e episcopais do séc. XVII. No séc. XVIII encontramo-lo codificado no Manual de pintura de Dionísio de Furná, que assim o descreve: “Cristo que abençoa com as duas mãos e, segurando sobre o peito o Evangelho, diz: Eu sou a videira, e vós os ramos; e ramos de videira que saem dele e os apóstolos engastados neles”2. Foti Kontoglou, por sua vez, confere, como título, à represen- tação o seguinte nome acrescentado: “Eu sou a Videira” e indica, como lugar da representação, as paredes do nártex da igreja.

O ícone aqui reproduzido oferece uma boa ilustração do tema evangélico. Seu formado médio (77 x 79 cm) destinava-o provavelmente a ser exposto à direita da “Bela Porta” da iconóstase; neste caso, também o ícone correspondente da Mãe de Deus devia ter uma representação adequada, em geral aquela da “Árvore de Jessé”: neste caso sobre os ramos da Árvore são representados, em torno de Maria, os profetas, que seguram nas mãos profecias.

O ícone representa Cristo em busto, na tipologia canônica do Pantocrator, embora com algumas adaptações. Cristo domina ao centro do quadro, e parece fazer parte do tronco da videira; em posição frontal, tem os braços erguidos em forma de convite e de bênção.

No seio traz um Evangelho aberto sobre as primeiras palavras da alegoria evangélica: “Eu sou a videira, vós sois os ramos, e meu Pai é o agricultor; todo sarmentos que em mim não…” (Jo 15,1-2).

Do tronco da videira partem grossos ramos, e destes, cobertos de folhas e de cachos, doze sarmentos que envolvem os doze apóstolos. Estes são divididos em dois grupos, que copiam a ordem presente geralmente na iconóstase; o grupo à direita de Cristo (à esquerda de quem olha) é formado por Pedro, isolado e colocado perto de Cristo; os outros apóstolos são, começando do alto: Marcos, João, André, Simão e Tomé; o grupo à esquerda de Cristo (à direita de quem olha) é forma- do por Paulo, isolado por sua vez e posto próximo a Cristo; os outros apóstolos são, começando de cima: Mateus, Lucas, Tiago, Bartolomeu e Filipe.

Os apóstolos são representados em busto: os evangelistas seguram livros abertos onde estão escritas as primeiras palavras do seu Evangelho: no livro segurado por Pedro se leem as primeiras palavras da sua carta; ao passo que no livro que Paulo segura estão escritas as primeiras palavras da sua carta aos Romanos.

As figuras dos apóstolos refletem os traços que a iconografia tradicional reserva a cada um, permitindo conhecer cada qual mesmo sem poder ler as iniciais dos seus nomes postos em correspondência da cabeça, fora da auréola.

Note-se que o pintor deixou vazio o espaço em cima do busto de Cristo; outros iconógrafos não deixarão de pintar aí Deus Pai que aparece numa nuvem e abençoa com ambas as mãos; entre o Pai e o Filho porão também uma pomba com as asas abertas, símbolo do Espírito Santo. Este último modo de fazer leva em conta a menção, no texto evangélico, do Pai de Jesus, apresentado como agricultor, e

Fonte: Ícones de Cristo – História e Culto – Georges Charib – Edit. Paulus

Christ “True Vine” (icon, about 1450)

Let us also see why our Savior compared himself to the vine.

“I am the true vine and the farmer is my Father.” In the vine of his body was hidden the sweetness of his divinity; Into the vine of his body was grafted the shoot and the branch of our humanity. From the vine of his body, the drink that quenched our thirst sprouted for us. From the sprig of his humanity rivers flowed to us by his grace.

The vine is silent when they harvest the grape, like our Lord when they judge him; the vine remains silent when it is stripped, like our Lord when he is insulted; the vine is silent when they prune it, as our Lord is silent when they kill him.

Instead of that ancient vine, which offered vinegar to its owner, a real vine emerged from the young woman’s bosom. This is the vine, which intoxicated men and possessed life; This is the vine, which, with its fruit, washes the world from iniquities.

It is the bunch that squeezed itself in the Cenacle, in the evening hour, and in the chalice was given to its disciples, which is the testimony of truth, because its wealth never diminishes.

CIRILLONA, Last Supper Speech

Jesus “True Vine”

The iconographic theme of Christ “True Vine” is inspired by the evangelical allegory of John 15:1ff. There Jesus equates himself to the vine, comparing his Father to the vinedresser, while his disciples are assimilated to the branches. Their union with the trunk is the condition for bearing fruit and being loved by the Father. Otherwise, they are cut, left to dry and thrown into the fire.

The iconographic illustration of the theme is relatively recent and seems to be prompted by the desire of iconographers to deal with new arguments that were totally ignored in the past, or at least barely treated until then. The first representations date back to the 17th century. XV and all appear to be after the fall of Constantinople into the hands of the Turks in 1453.

The origin was the island of Crete, where many artists had taken refuge fleeing the Turks, and the monasteries of Mount Athos, which offered them enormous spaces to decorate frescoes and icons.

The theme, which emerged in the 19th century. XV, becomes frequent in frescoes and icons of the century. XVI and multiplied in the century. XVII; It is also found in many priestly and episcopal vestments from the 16th century. XVII. In the century. XVIII we find it codified in the Painting Manual of Dionísio de Furná, which describes it as follows:

“Christ who blesses with both hands and, holding the Gospel on his chest, says: I am the vine, and you are the branches; and branches of vine coming out of him and the apostles embedded in them”2. Foti Kontoglou, in turn, gives the representation the following added name as its title: “I am the Vine” and indicates, as the place of representation, the walls of the church’s narthex.

The icon reproduced here offers a good illustration of the evangelical theme. Its medium shape (77 x 79 cm) was probably intended to be exposed to the right of the “Beautiful Door” of the iconostasis; In this case, the corresponding icon of the Mother of God should also have an appropriate representation, generally that of the “Tree of Jesse”: in this case, the prophets are represented on the branches of the Tree, around Mary, holding the hands prophecies.

The icon represents Christ in bust, in the canonical typology of the Pantocrator, although with some adaptations. Christ dominates the center of the painting, and appears to be part of the vine trunk; in a frontal position, his arms are raised in the form of an invitation and blessing. Inside it is a Gospel open to the first words of the evangelical allegory: “I am the vine, you are the branches, and my Father is the vinedresser; all the branches that are not in me…” (John 15:1- two).

Thick branches come from the trunk of the vine, and from these, covered with leaves and bunches, twelve branches envelop the twelve apostles.

These are divided into two groups, which copy the order generally present in the iconostasis; the group to the right of Christ (to the left of the viewer) is formed by Peter, isolated and placed close to Christ; the other apostles are, starting from above: Mark, John, Andrew, Simon and Thomas; the group to the left of Christ (to the right of the viewer) is formed by Paul, isolated in turn and placed close to Christ; the other apostles are, starting from the top: Matthew, Luke, James, Bartholomew and Philip.

The apostles are represented in busts: the evangelists hold open books where the first words of their Gospel are written: in the book held by Peter the first words of his letter are read; while in the book that Paul holds are written the first words of his letter to the Romans.

The figures of the apostles reflect the traits that traditional iconography reserves for each one, allowing us to know each one even without being able to read the initials of their names placed in correspondence of the head, outside the halo.

Note that the painter left the space above the bust of Christ empty; other iconographers will not fail to paint there God the Father who appears in a cloud and blesses with both hands; Between the Father and the Son they will also place a dove with outstretched wings, a symbol of the Holy Spirit.

This last way of doing things takes into account the mention, in the evangelical text, of the Father of Jesus, presented as a farmer, and

Source: Ícones de Cristo – História e Culto – Georges Charib – Edit. Paulus

Produzido por

Consulte a Agenda do Museu a partir de 2025 e o visite quando receber sua confirmação de visita em seu email ou whatsapp.

Por se tratar de um museu particular, é necessário se cadastrar na Comunidade MuMi e customizar sua visita.

Criação e Tecnologia: Clayton Tenório @2025 MuMi – Museu Mítico