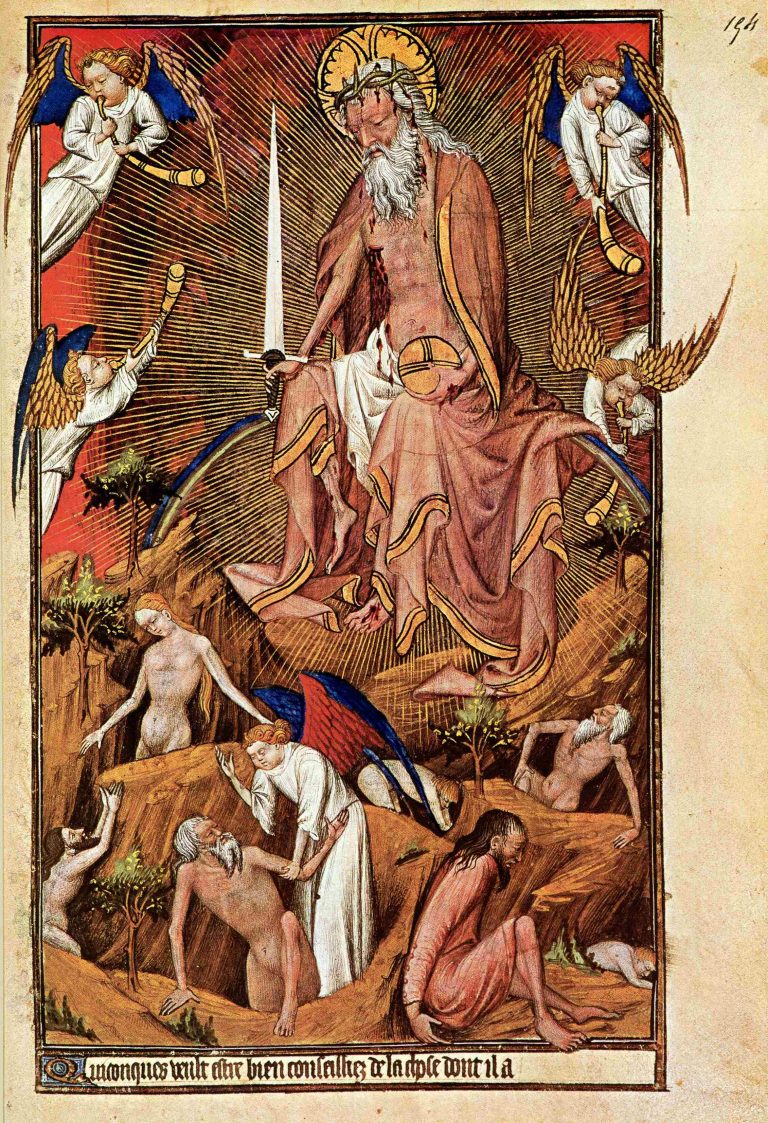

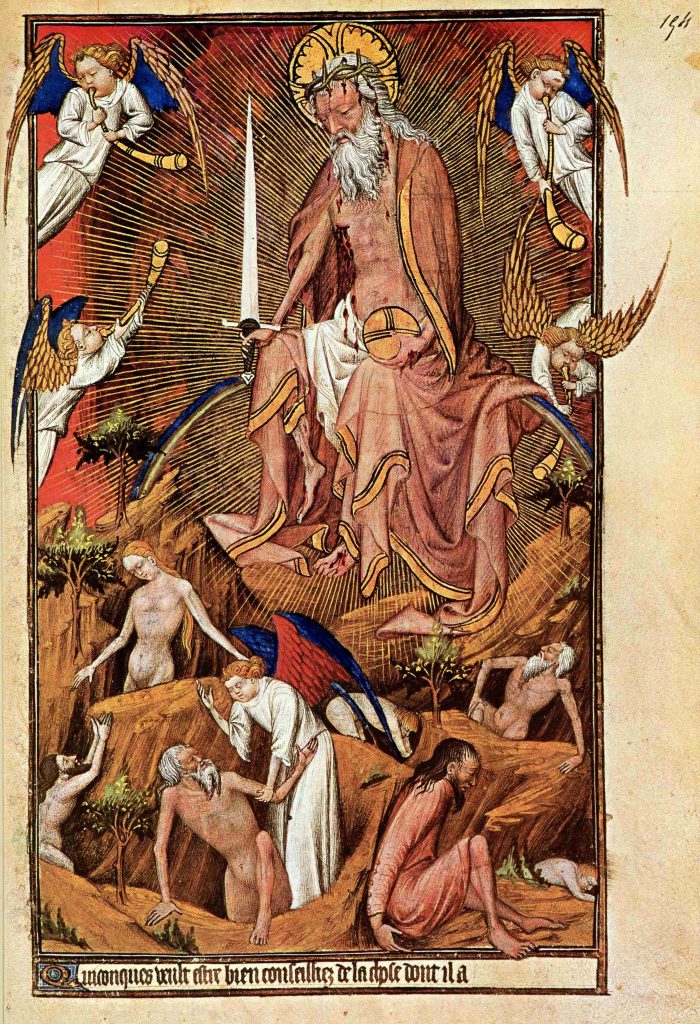

Jesus Cristo em Julgamento – The Grandes Heures de Rohan – Uso de Paris, França – 1420

29 x 20,8 cm (11 × 8 pol.), 239ss. 11 miniaturas de página inteira e 54 miniaturas de meia página, 470 miniaturas menores nas bordas. Biblioteca Nacional, Paris, ms. lat. 9471

Este grande livro de orações de Anjou, que leva o nome de Rohan devido a um acidente de propriedade posterior, é totalmente marcado pela poderosa personalidade do artista conhecido por nós apenas como o Mestre Rohan.

O Juízo Final nestas Grandes Heures não ocorre no Ofício dos Mortos, como é costume, mas nos Sete Pedidos.

Estas invocações a Cristo Salvador, atribuídas ao Venerável Beda, são introduzidas por uma oração que, se recitada diariamente, preservava o suplicante da morte súbita, sem confissão ou de qualquer outra forma violenta.

Hoje a morte súbita é considerada quase desejável.

Para os nossos antepassados medievais foi uma catástrofe, uma vez que os privou da oportunidade de fazer confissões, ainda que inadequadamente e no último momento, por vidas mal desperdiçadas, e de serem rejeitados.

Cristo está sentado sobre um arco-íris segurando uma espada erguida para indicar que ele é realmente um juiz.

Ele é mostrado como velho, não jovem. O Mestre Rohan parece ter preferido a idade à juventude, mas aqui também pode ter tido conhecimento da doutrina teológica de que o Juízo Final une Deus Pai e Deus Filho, duas pessoas da Trindade, permanentemente numa só. Cristo parece aceitar com angústia a sua dolorosa tarefa. Um quarteto de anjos anuncia o terrível acontecimento com toques de trombetas primitivas.

Finamente compostos, são curiosamente humanos em gestos e expressões; ao contrário de Cristo, eles parecem quase saborear a sua tarefa. Representantes do homem caído rastejam dolorosamente para fora de seus túmulos.

À esquerda, Eva parece reconhecer Adão.

A figura mais impressionante é o homem de cabelos escuros que se agacha numa atitude de total miséria e desespero.

Será que a sua condição vestida indica, como foi sugerido, que ele simboliza os que estarão vivos no Dia do Juízo?

O Duque de Anjou, no oeste da França, adjacente à Bretanha, foi distribuído en apanage (ver p. 53) três vezes pelos reis franceses medievais.

A Primeira Casa incluía Geoffrey de Anjou, que fundou a linha inglesa Plantageneta no século XII.

A Segunda Casa começou no século XIII com Carlos, irmão de São Luís IX, e Rei da Sicília (ele perdeu a Sicília para os espanhóis nas Vésperas Sicilianas de 1284, mas manteve Nápoles).

Seus descendentes, reis titulares da Sicília, conquistaram muitas coroas dos escombros políticos das Cruzadas enquanto lutavam entre si pela posse de Nápoles.

Em 1360, a linha masculina francesa falhou, e uma Terceira Casa de Anjou começou com o segundo filho do rei João II de França (le Bon), Luís, que também foi declarado herdeiro de Nápoles e do título siciliano pela sua parente, a rainha Joana 1. Ele e seus descendentes se destacaram por sua ambição, energia, talento e gosto artístico.

Seu filho Luís II de Anjou, que o sucedeu em 1384 aos sete anos de idade, tinha a reputação de um “príncipe justo, erudito e afável”.

Ele morreu em 1417 e é seu Livro de Horas favorito. que pertencera ao seu avô, D. João II, foi colocado sobre o seu peito enquanto ele jazia em estado.

Dele idoso passou a maior parte de sua curta vida na Itália; seu filho mais novo era o famoso bon rot René, dois de cujos Livros de Horas são ilustrados aqui (pp. 86-93).

Mas foi a viúva de Luís II, Yolanda, filha de João I de Aragão e conhecida durante a sua vida como Rainha da Sicília, que agora se tornou uma grande potência em França.

Após a morte de Carlos VI em 1422, sete anos após o debículo de Agincourt, os ingleses reduziram temporariamente seu filho Carlos VII (a quem até sua própria mãe, a infame Rainha Isabel, reputada amante de Luís de Orleans, chamava de soi-disant Delfim) a uma existência precária na antiga capital de John of Berry, Bourges.

Durante esses anos, Yolanda se destacou; ela casou sua filha Marie com o rei e até sua morte em 1442 foi a verdadeira líder do partido legitimista na França.

Iolanda não teve sucesso em reconciliar as suas próprias Casas de Anjou e Aragão, que lutaram por Nápoles, mas mostrou grande habilidade em separar os vassalos feudais franceses da aliança inglesa.

Ela nunca é mencionada pelos cronistas da Borgonha, porque os angevinos apoiavam os odiados rivais dos borgonheses, os Armagnacs.

É quase certo que o Grandes Heures foi feito para Yolanda ou para um de seus filhos; a forma masculina do Obsecro te e A intemerata não é uma evidência conclusiva de que o primeiro proprietário tenha sido um homem (mesmo as Grandes Heures de Ana da Bretanha têm estas orações inexplicavelmente na forma masculina).

Foi sugerido que as iluminuras refletem a atmosfera dos anos dolorosos entre Agincourt (1415) e a milagrosa restauração da moral francêsa por Joana d’Arc quinze anos depois.

Presume-se geralmente que o Mestre Rohan foi o chefe de uma oficina movimentada, patrocinada pela Casa de Anjou e aparentemente localizada em diferentes épocas em Paris, Angers, Bourges, Troyes, Bretanha, Provença e outros lugares.

Sua influência neste manuscrito é forte, mas nem todas as miniaturas de página inteira são inteiramente de sua autoria; talvez ele próprio não fosse um pintor de livros profissional?

Ele parece ter conhecido o trabalho dos Mestres Boucicaut e Bedford e dos irmãos Limbourg. O seu estilo maduro é, no entanto, tão convincente e peculiar que os estudiosos procuraram as suas fontes não só em Paris, mas também na Catalunha (o país da sua patrona Yolanda de Aragão), na Provença, no norte de França e na Alemanha, com uma possível contribuição de Bolonha.

As onze miniaturas de página inteira que sobreviveram (faltam a Adoração dos Reis Magos e outras ilustrações essenciais em um Livro de Horas) conferem ao manuscrito seu caráter único e misterioso.

Distorção e violência combinam-se com um inquietante. Avançado em alguns aspectos, em outros o Mestre Rohan era quase antiquado, mostrando pouco interesse pela perspectiva ou pela paisagem naturalista; ele estava em grande parte imune às novas influências da Itália correntes em Paris.

Na sua representação de cenas e encontros tradicionais, os rostos do elenco sagrado são tão ansiosos, melancólicos e até feios quanto os dos participantes humanos.

Ele foi um pintor de ideias: especificamente, de ideias religiosas.

A componente religiosa nas obras de arte, distinta da iconografia religiosa, é uma questão que os historiadores da arte parecem não querer examinar. No entanto, em períodos em que a arte era motivada pela religião, encontramos por vezes obras que apresentam uma qualidade transcendental demasiado enfática para ser explicada apenas pela iconografia, pela estética ou pela análise estilística.

Uma experiência pode ser definida como religiosa se compreender três elementos: um sentimento de admiração diante do desconhecido, um sentimento de inquietação e muitas vezes de culpa pela inadequação de nossa dotação humana, e um desejo de algum tipo de participação ou identificação com uma realidade maior.

Todos os três estão presentes na obra do Mestre Rohan.

Um mistério final é a história posterior das Grandes Heures.

Em várias páginas, as armas da família Rohan da Bretanha, sete mastros de ouro (ou diamantes) sobre fundo vermelho, parecem ter sido adicionadas.

As Grandes Heures podem ter chegado à sua posse através de uma ligação dinástica, tal como outro manuscrito de Anjou, conhecido como Horas de Isabella Stuart (pp. 114-17), provavelmente passou para a Casa da Bretanha na década de 1440.

Ou, como foi engenhosamente sugerido (não há provas), o precioso manuscrito pode ter feito parte do enorme resgate pago pelo filho de Yolanda, René, a Filipe, o Bom da Borgonha, em 1437: o aliado de Filipe, Antoine de Vaudemont, vencedor sobre René em Bulgnéville em 1431, teve uma filha que se casou com Alain IX, Visconde de Rohan.

Como tantas vezes acontece com manuscritos e outros livros, gostaríamos que alguém tivesse pensado em acrescentar uma breve nota de propriedade num momento em que tal informação parecia óbvia demais para valer a pena registrar.

As Grandes Horas de Rohan continuam sendo um dos mais intrigantes e contundentes em termos de expressão religiosa de todos os Livros de Horas. É apropriado, visto que a própria religião é misteriosa, que haja tantos mistérios em torno do livro.

Source: The Book of Hours – Park Lane New York, 1977, pg. 83

Divulgado por:

Consulte a Agenda do Museu a partir de 2025 e o visite quando receber sua confirmação de visita em seu email ou whatsapp.

Por se tratar de um museu particular, é necessário se cadastrar na Comunidade MuMi e customizar sua visita.

Criação e Tecnologia: Clayton Tenório @2025 MuMi – Museu Mítico