Ecce Home – Hieronymous Bosch

Eis o Homem disse Pilatos…

Em algum lugar em meados da década de 1490, Bosch pintou o Ecce Homo (p. 33, Cat. 4), agora em Frankfurt am Main.

O patrono era um membro da elite social, também representada nas fileiras da Irmandade. Se ele era de fato um membro, no entanto, não pode mais ser esclarecido, uma vez que as figuras do doador foram raspadas e pintadas e só foram descobertas durante a restauração mais recente do painel, em 1983.

O casal doador e seus sete filhos um deles um monge dominicano e seis filhas são agora visíveis apenas como figuras sombrias. O tema pictórico é retirado dos Evangelhos (Mateus 27:11-26; Marcos 15:2-15; Lucas 23:2-7, 13:25; João 18:28 e 19:16).

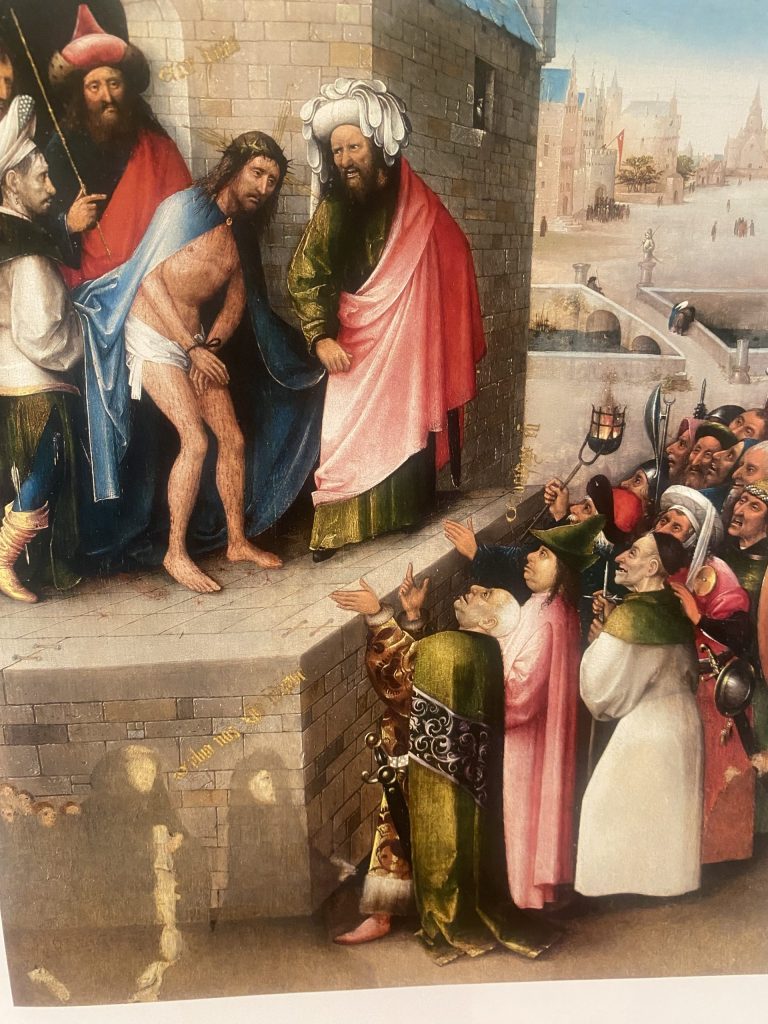

Jesus, espancado e coroado de espinhos, é exibido em frente ao palácio pelo governador romano Pôncio Pilatos, que convida a multidão reunida a escolher se ele deve executar Jesus ou Barrabás.

De pé em um pódio elevado sob o arco de uma porta à esquerda, vestido de preto e vermelho e segurando seu bastão na mão, Pilatos apresenta Jesus o foco óptico da imagem à multidão faminta.

O Cristo humilhado, sangrando e curvado é escoltado por um guarda de rosto pálido e turbante à direita e um cúmplice elegantemente vestido à esquerda, ambos segurando o e conduzindo o pelas dobras de sua capa azul.

O diálogo que se segue também pode ser lido em três inscrições em letras douradas, que o artista incorporou no painel. Pilatos anuncia “Ecce Homo” (“Eis o Homem!”), em resposta ao qual a multidão colorida, vestida com trajes fantásticos, clama “Crucifige eum” (“Crucifique o!”).

Diretamente abaixo de Cristo, o pai e o filho mais velho da família doadora oram: “Salva nos xp[=Cristo]e redentor” (“Salva nos, Cristo Redentor”).

A justaposição de imagens e inscrições deixa clara a orientação escatológica da obra: Ecce Homo expressa o fervoroso apelo para que Deus liberte as almas do doador e de sua família no Dia do Juízo, e assim garanta a todos um lugar no Paraíso.

Também aqui a paisagem aparece como um “mundo” ambivalente com elementos bizarros e ameaçadores. O cenário arquitetônico é em grande parte de carácter europeu, mas também inclui características orientais, como a bandeira vermelha do Império Otomano (p. 41).

Também nesta pintura encontramos figuras diminutas de viajantes ou de pessoas passeando, como Bosch também empregou em outras obras. Estes incluem dois de costas para o observador e olhando para as profundezas da imagem, como na Crucificação (Cat. 1) = e São Jerônimo (Cat. 2; Fischer 2009, pp. 278 279).

Ecce Home – Hieronymous Bosch

Hold The Man said Pilates…

Somewhere in the middle of the 1490s Bosch painted the Ecce Homo (p. 33, Cat. 4) now in Frankfurt am Main. The patron was a member of the social elite, as also represented in the ranks of the Brotherhood.

Whether he was indeed a fellow member, however, can no longer be clarified, since the donor figures were scraped off and overpainted and were only uncovered during the panel’s most recent restoration, in 1983.

The donor couple and their seven sons – one of them a Dominican monk – and six daughters are now only visible as shadowy figures. The pictorial theme is taken from the Gospels (Matthew 27:11-26; Mark 15:2-15; Luke 23:2-7, 13-25; John 18:28- 19:16).

Jesus, beaten and crowned with thorns, is paraded in front of the palace by the Roman governor Pontius Pilate, who invites the assembled crowd to choose whether he should execute Jesus or Barabbas. Standing on a raised podium beneath the arch of a doorway on the left, robed in black and red and holding his staff of office in his hand, Pilate presents Jesus – the optical focus of the picture – to the hungry mob.

The humiliated, bleeding and bowed Christ is escorted by a pale-faced guard in a turban on the right and a smartly dressed accomplice on the left, both holding and leading him by the folds of his blue cape. The ensuing dialogue can also be read in three in- scriptions in gold lettering, which the artist has incorporated within the panel.

Pilates announces “Ecce Homo” (“Behold the Man!”), in response to which the colourful crowd, clothed in fantastical costumes, clamours “Crucifige eum” (“Crucify him!”).

Directly beneath Christ, the father and eldest son of the donor family pray: “Salva nos XP Christ Redemptor” (“Save us, Christ the Redeemer”).

The juxtaposition of image and inscriptions makes plain the eschatological orientation of the work: Ecce Homo expresses the fervent plea that God will deliver the souls of the donor and his family on the Day of Judgement, and thus secure them all a place in Paradise.

In compositional terms, Bosch’s Ecce Homo is related to a woodcut of the same subject (p. 32) by Israhel van Meckenem the Younger (c. 1440-1503), an important engraver active in Bocholt in Westphalia, only about 62 miles from Hertogenbosch.

Bosch’s treatment of the landscape is distinctly different, however, from that of earlier artists. Here, too, the landscape appears as an ambivalent “world” with bizarre and menacing elements.

The architectural backdrop is largely European in character, but also includes Oriental features such as the red flag of the Ottoman Empire (p. 41).

In this painting, too, we find the diminutive figures of travellers or people out for a walk, such as Bosch also employed in other works. These include two with their backs to the viewer and looking into the depths of the picture.

Source: Heronimus Bosch, Taschen.

Produzido por

Consulte a Agenda do Museu a partir de 2025 e o visite quando receber sua confirmação de visita em seu email ou whatsapp.

Por se tratar de um museu particular, é necessário se cadastrar na Comunidade MuMi e customizar sua visita.

Criação e Tecnologia: Clayton Tenório @2025 MuMi – Museu Mítico